Mediterranean Flour Moth (Ephestia kuehniella)

If you open a bag of flour and find fine silk webbing or small gray moths flying out, you may be dealing with the Mediterranean flour moth (Ephestia kuehniella).

If you open a bag of flour and find fine silk webbing or small gray moths flying out, you may be dealing with the Mediterranean flour moth (Ephestia kuehniella).

This small but destructive pest is one of the most common insects infesting mills, bakeries, and pantries worldwide.

I’ve seen it countless times in my career — perfectly clean flour silos ruined by a few unnoticed larvae. It’s not the adult moth that causes the damage but its larvae, which feed and spin sticky silk through the food, making it clump together and turn unusable.

Unlike Indian meal moths or rice moths, which infest home pantries more often, the Mediterranean flour moth is especially notorious in industrial food facilities where flour dust and warmth create perfect breeding grounds.

Identification

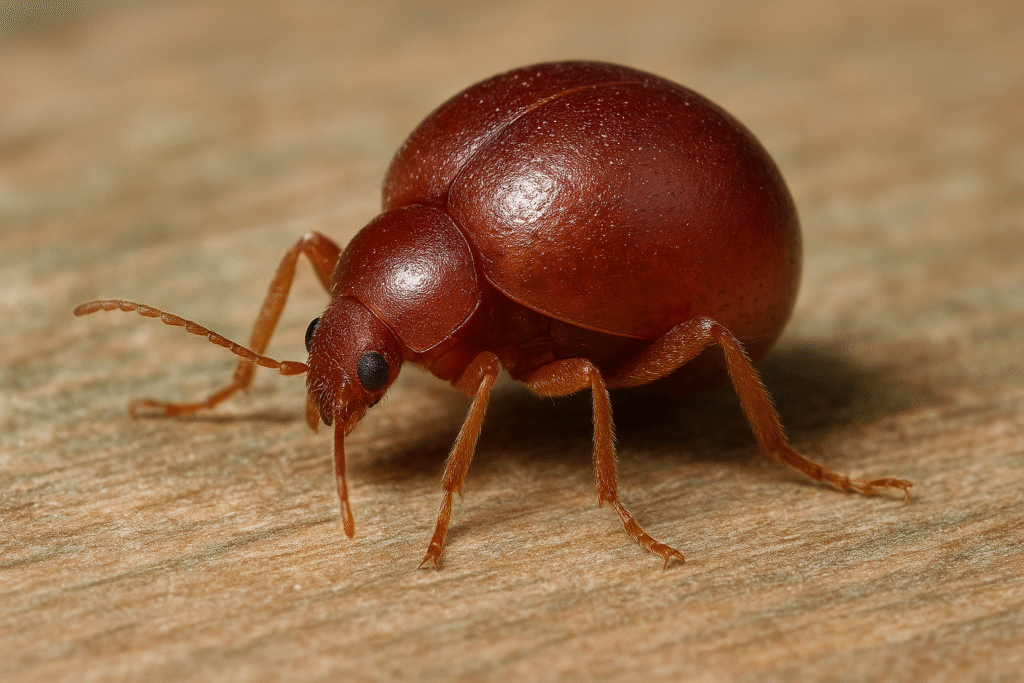

The adult Mediterranean flour moth is small and often goes unnoticed until it becomes a full infestation.

Main features:

-

Scientific name: Ephestia kuehniella

-

Common name: Mediterranean flour moth

-

Family: Pyralidae

-

Adult size: 10–12 mm body length; 20–25 mm wingspan

-

Color: Pale gray wings with wavy darker lines; light body

-

Larvae: White to pinkish caterpillars with brown heads, up to 12 mm long

-

Pupa: Found in silken cocoons attached to walls, machinery, or packaging

Typical signs:

-

Silky webbing on flour surfaces

-

Clumped or compacted flour

-

Fine dust and moths flying near ceiling lights

-

Pupae in cracks, corners, or machinery

When you see flour “sticking together” for no reason, it’s often not humidity — it’s this moth.

Biology and Ecology

The life cycle of Ephestia kuehniella is quite simple but extremely efficient.

1. Eggs: Females lay between 100–500 eggs directly on flour or nearby surfaces.

2. Larvae: The larvae hatch within a few days and begin feeding immediately, creating silk tunnels through flour, bran, and cereal products.

3. Pupae: When mature, they crawl away to pupate in crevices, cracks, or inside machines.

4. Adults: They live for about 1–2 weeks, long enough to reproduce.

The full cycle takes 4–6 weeks in warm temperatures (25–30°C), but in cool climates it can take several months.

Preferred environment:

-

Temperature: 20–30°C

-

Humidity: 65–75%

-

Food sources: Wheat flour, cornmeal, bran, pasta, biscuits, dry animal feed

The larvae avoid light and prefer compacted, undisturbed flour. That’s why infestations often start deep inside silos or under old stock.

Global Distribution

As its name suggests, this moth originated in the Mediterranean region, but today it’s found worldwide, especially where flour is produced or stored.

-

Europe: Common in southern and central regions, especially Italy, Greece, Spain, and France.

-

North America: Found in bakeries, mills, and even households.

-

South America: Major problem in Brazil and Argentina’s flour industries.

-

Asia and Australia: Widespread in grain and pasta storage facilities.

Its success is linked to global food transport and the fact that even a few eggs can survive inside flour bags shipped long distances.

Risks and Damage

The Mediterranean flour moth doesn’t carry disease, but its presence causes major economic losses.

Main damage includes:

-

Contamination: Larval silk, droppings, and shed skins ruin food quality.

-

Clogged machinery: Webbing blocks flour sifters, pipes, and elevators.

-

Loss of product: Infested flour becomes unsuitable for consumption.

-

Secondary pests: Infestation attracts grain mites and warehouse beetles.

In commercial bakeries, production may stop completely during a moth outbreak — a single batch of contaminated flour can spoil tons of product.

Signs of Infestation

Early detection is critical. Common indicators include:

-

Small moths flying near lights or flour sacks.

-

Fine silk webbing in stored flour or bran.

-

Sticky flour clumps or tunnels inside bags.

-

Pupae stuck to walls, shelves, or machinery.

-

A faint, musty smell from old or contaminated stock.

If you see moths near your ceiling or storage bins, the larvae are already active somewhere.

Control Methods

1. Inspection

Check all stored flour, cereal, and dry goods. Discard any products that show clumping, webbing, or movement. Examine even unopened bags — larvae can chew through thin paper or plastic packaging.

2. Cleaning

Thorough cleaning is essential. Vacuum all shelves, cracks, and behind equipment. Remove flour dust from corners, beams, and machines. Wash surfaces with hot, soapy water and dry well.

Even a few crumbs can sustain new larvae.

3. Storage Management

-

Keep flour in airtight containers.

-

Rotate stock (first-in, first-out system).

-

Avoid storing products near heat sources or high humidity.

-

Don’t mix new flour with old stock.

4. Freezing or Heating

-

Freeze infested flour for 4–5 days at -18°C.

-

Alternatively, heat at 60°C for one hour if possible.

5. Monitoring

Use pheromone traps designed for Ephestia kuehniella. These attract and capture males, helping to monitor infestation levels.

Traps don’t stop an outbreak, but they help identify the right moment for cleaning or treatment.

6. Insecticide Use

In home settings, insecticides are rarely needed.

In factories, pest control professionals may apply residual sprays, fogging, or heat treatments — always when food is removed or sealed.

Avoid spraying directly on flour or food-contact surfaces.

Advanced Approaches

Modern pest management focuses on prevention rather than chemical control.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) combines several strategies:

-

Pheromone-based mating disruption — confuses males, reducing breeding.

-

Biological control — using Trichogramma wasps to parasitize moth eggs.

-

Modified atmosphere storage — using carbon dioxide or nitrogen to suffocate all life stages.

-

Structural maintenance — sealing cracks and installing air curtains at entry points.

In mills, temperature control and regular emptying of silos are crucial. I often recommend deep cleaning twice a year, even when no moths are visible — prevention is always cheaper than fumigation.

Cultural and Historical Context

The Mediterranean flour moth has been known since the early 1900s as one of the first insects to infest industrial flour mills.

It was actually one of the first pests used in laboratory studies on stored grain insects, which led to early pest control research in Europe.

Historically, millers in southern Europe fought these moths using natural methods: they stored flour in clay jars sealed with olive oil, or burned bay leaves and sulfur to repel insects.

While we’ve replaced smoke with science, the principle remains the same — prevention, cleanliness, and vigilance.

FAQ Section

1. What is the scientific name of the Mediterranean flour moth?

It’s Ephestia kuehniella, a species of the Pyralidae family.

2. Do Mediterranean flour moths bite humans?

No, they don’t bite or sting. Their larvae feed only on dry food materials.

3. How long do they live?

Adults live for about 1–2 weeks. The complete life cycle takes 4–8 weeks depending on temperature.

4. What foods do they infest?

Mainly flour, bran, cereals, dried grains, and animal feed. Occasionally, they infest nuts and seeds.

5. How can I get rid of them naturally?

Clean thoroughly, discard infested materials, and store all food in airtight containers. Freezing flour for several days is very effective.

6. Are pheromone traps enough to stop them?

No, traps only catch males and help monitor activity. You still need to clean, inspect, and store properly to eliminate larvae.

7. Can these moths come back after cleaning?

Yes, if even a few eggs or larvae remain hidden in cracks or equipment. Follow-up inspections are important.

Final Thoughts

The Mediterranean flour moth is one of those pests that quietly build up over time — you rarely notice them until the damage is visible. I’ve seen this insect ruin entire flour stocks in bakeries and mills, even when everything looked “clean.” What starts as a few webbed clumps in a corner can turn into a full-scale infestation if ignored for a few weeks.

The key lesson I always tell clients: this moth loves stability — constant temperature, stored food, and dust. Break that cycle and it disappears. Rotate your stock, deep-clean machines, and keep humidity low. If you run a bakery or mill, schedule preventive cleanings every few months and use pheromone traps to track activity.

Once the Mediterranean flour moth gets inside, chemical treatments alone rarely solve the problem. The combination of hygiene, monitoring, and sealing entry points is what truly keeps them under control. Prevention is always the cheapest form of pest control — and the one that keeps your production safe year-round.

Learn more about other Stored Product Pests

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only. Pest control laws and approved chemicals vary by country. For best results and legal safety, we strongly recommend contacting a licensed pest control professional in your local area. Always make sure that the pest control technician is properly certified or licensed, depending on your country’s regulations. It’s important to confirm that they only use approved products and apply them exactly as instructed on the product label. In most places in Europe, UK, or USA, following label directions is not just best practice—it’s the law.

Author

Nasos Iliopoulos

BSc Agronomist & Certified Pest Control Expert

Scientific Director, Advance Services (Athens, Greece)

Licensed Pest Control Business – Ministry of Rural Development & Food (GR)

References

-

Penn Uneversity - Mediterranean Flour Moth

-

University of Minnesota - Mediterranean Flour Moth