Cheese Mites (Tyrophagus casei): Identification, Risks, and Professional Control

If you ever inspected an aging cheese and saw a fine layer of powder that seemed to move under the microscope, you were probably looking at cheese mites (Tyrophagus casei). These microscopic pests are part of the same family as grain mites (Acarus siro) and thrive in food production and storage areas with high humidity.

If you ever inspected an aging cheese and saw a fine layer of powder that seemed to move under the microscope, you were probably looking at cheese mites (Tyrophagus casei). These microscopic pests are part of the same family as grain mites (Acarus siro) and thrive in food production and storage areas with high humidity.

I have seen infestations in cheese factories, grocery warehouses, and cold rooms where workers couldn’t understand why the cheese developed a dusty crust and an unpleasant odor. While some traditional cheese makers actually use these mites intentionally for surface ripening, in commercial or domestic settings, they are a serious sanitation and quality problem.

Understanding their biology and behavior is the first step to stopping them from spreading through your food stock.

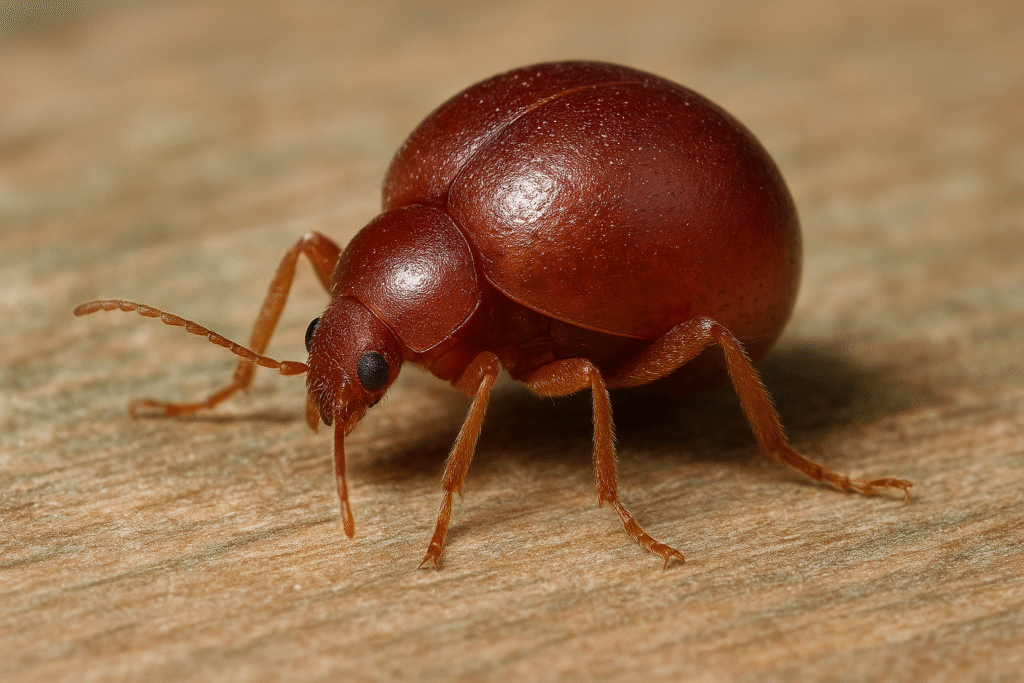

Identification

Cheese mites are extremely small, measuring 0.3–0.5 mm in length. You can barely see them without magnification, but large colonies look like moving dust or a fine grayish powder.

Key characteristics:

-

Oval, pale white or translucent body.

-

Eight legs (they are true mites, not insects).

-

Move slowly across food surfaces.

-

Leave behind fine dust made of shed skins and fecal particles.

Under a microscope, they appear similar to grain mites (Acarus siro), and the two species are often found together in the same environment.

Biology and Ecology

Tyrophagus casei thrives in warm, humid environments (over 70% relative humidity, 20–25°C).

They feed on protein-rich organic matter — cheese, dry milk, flour, grains, and even dried meat.

-

Egg stage: Females lay about 20–40 eggs per batch.

-

Larvae and nymphs: Develop within 1–2 weeks, depending on temperature.

-

Adults: Live up to 3–6 weeks, producing several generations per month.

Populations can explode rapidly when conditions are right. In just a few weeks, one unnoticed contamination can turn into a visible layer of mites.

Humidity is the key driver — reduce it, and you cut the population’s ability to reproduce.

Global Distribution

Cheese mites are found worldwide — anywhere food is processed or stored.

They are particularly common in:

-

Cheese aging rooms (Europe, especially in France, Italy, and Switzerland).

-

Dairies and cold storage facilities.

-

Pantries and domestic kitchens with old food stock.

-

Feed and grain stores (shared habitats with flour beetles and pantry moths).

They are often introduced via contaminated equipment, packaging, or raw materials such as flour or powdered milk. Once inside, they spread quickly to other products.

Risks and Damage

While cheese mites don’t bite humans, their presence causes several serious problems:

1. Product contamination

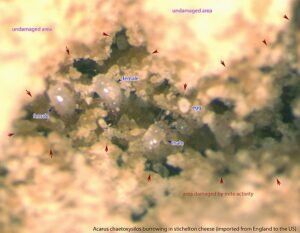

They burrow into the surface of cheese, causing powdering and pitting. Infested cheeses often develop a musty or ammonia-like odor.

2. Economic loss

Large infestations can ruin entire batches of aged cheese, leading to recalls or destroyed stock.

3. Allergies and respiratory irritation

Workers exposed to high mite populations may develop allergic reactions or “grocer’s itch” — a mild dermatitis caused by contact with the mites or their debris.

4. Cross-infestation

They can easily move to other dry goods, including grains and cereals. This links them directly to pests like grain mites, flour beetles (Tribolium spp.), and pantry moths (Ephestia kuehniella).

Signs of Infestation

-

Fine dust or powder on cheese surfaces or wooden shelves.

-

Musty smell or off-flavor in aged cheese.

-

Gray patches or crust forming on cheese rinds.

-

Visible movement when examining under light or magnification.

-

Increased humidity and condensation inside aging rooms or storage areas.

In advanced infestations, you can sometimes even hear a faint crackling sound from the mites moving in dense clusters on cheese surfaces.

Control Methods

1. Sanitation and Hygiene

Good hygiene is the foundation of control.

-

Clean and sanitize all surfaces, racks, and equipment regularly.

-

Avoid accumulation of food residues and organic dust.

-

Discard old cheese stock or contaminated packaging immediately.

2. Temperature and Humidity Control

Maintain storage areas below 60% relative humidity and below 18°C if possible.

Mites cannot reproduce effectively under these conditions.

3. Air Circulation

Ensure proper airflow and use dehumidifiers to reduce condensation on shelves and walls.

4. Physical Cleaning

Use vacuum cleaners with HEPA filters to remove mite dust and prevent spreading.

Avoid sweeping, as it only redistributes them into the air.

5. Chemical Control (Professional Use Only)

In severe infestations, use approved residual insecticides or fumigation treatments by licensed professionals.

Always avoid direct contact with food surfaces and packaging materials.

Products based on pyrethrins, permethrin, or silicon dioxide dusts may be used for non-food contact areas.

6. Regular Inspection

Monitor food stock using traps or microscope sampling. Once mites appear, act immediately before the population becomes visible.

Advanced Approaches

Professionals may use Integrated Pest Management (IPM) combining:

-

Environmental control (humidity and temperature reduction).

-

Routine monitoring with sticky traps.

-

Scheduled sanitation audits.

-

Periodic disinfection of storage rooms with hot dry air or ozone.

In cheese factories, the challenge is balancing control with product quality — since some traditional cheeses (like Mimolette or Milbenkäse) intentionally use mites for ripening. In such cases, hygiene zones must be separated to avoid cross-contamination with clean areas.

Cultural and Historical Context

Cheese mites have been known since ancient times. Historical records from Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries describe “cheese dust” ruining merchants’ stock.

Ironically, humans also learned to use these mites. In certain regions of France and Germany, traditional cheesemakers intentionally let Tyrophagus casei colonize cheeses like Mimolette or Milbenkäse, developing their distinctive taste and texture.

However, outside of those specialized products, the same species is considered a contaminant. Today, global hygiene standards no longer allow natural mite-ripening in most industrial facilities due to allergen and food safety concerns.

FAQ: Cheese Mites

Q1: Are cheese mites harmful to humans?

A: Not directly, but they can cause allergic reactions and contaminate food products.

Q2: Can you eat cheese infested with mites?

A: No. Even though some traditional cheeses use mites intentionally, uncontrolled infestations are unsanitary and unsafe.

Q3: How do cheese mites spread?

A: Through contaminated food, packaging, or equipment. High humidity allows them to multiply and spread to nearby products.

Q4: What’s the difference between cheese mites and grain mites?

A: Both belong to similar families, but cheese mites (Tyrophagus casei) prefer protein-rich products like cheese, while grain mites (Acarus siro) target dry cereals and flours.

Q5: Do insecticides kill cheese mites?

A: Yes, but only under professional supervision. Using chemicals around food requires certified application and safety measures.

Q6: How can I prevent cheese mite infestations?

A: Keep humidity low, inspect food stock regularly, and maintain strict hygiene in storage areas.

Final Thoughts

In pest control, cheese mite infestations are one of the most underestimated problems in food storage. Because they’re so small, most people notice them only when the cheese surface already looks dusty or ruined.

From my experience treating dairies, cold rooms, and small grocery stores, the most common mistake is ignoring humidity control. You can clean, sanitize, and even spray, but if the humidity stays above 70%, these mites will come back fast.

For anyone working in cheese aging, bakeries, or storage facilities, the best defense is environmental discipline — regular inspections, humidity checks, and strict product rotation. When infestations reach the visible stage, chemical treatment should always be handled by a licensed pest control professional to avoid contaminating food or harming workers.

Even though these creatures played a strange role in cheese history, in today’s regulated food production they’re a clear sign of poor storage hygiene — not tradition.

Learn more about other Stored Product Pests

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only. Pest control laws and approved chemicals vary by country. For best results and legal safety, we strongly recommend contacting a licensed pest control professional in your local area. Always make sure that the pest control technician is properly certified or licensed, depending on your country’s regulations. It’s important to confirm that they only use approved products and apply them exactly as instructed on the product label. In most places in Europe, UK, or USA, following label directions is not just best practice—it’s the law.

Author

Nasos Iliopoulos

BSc Agronomist & Certified Pest Control Expert

Scientific Director – Advance Services (Athens, Greece)

Licensed Pest Control Business – Ministry of Rural Development & Food (GR)

References

-

Hughes, A.M. (1976). The Mites of Stored Food and Houses. Technical Bulletin, Ministry of Agriculture, UK.

-

Zdarkova, E. (1998). Acarid Mites Infesting Stored Products. Journal of Stored Products Research, 34(3).

-

Robertson, J., & Forbes, A. (2019). Mite Control in Food Production Facilities. Pest Management Science.

-

Leclercq, J. (2003). Cheese Mites and Traditional Cheese Ripening. Food Microbiology, 20(3).

-

FAO (2021). Pest Management in Food Storage and Processing Facilities. Food and Agriculture Organization Report.