Ticks: Identification, Biology, Risks, and Control of These Blood-Feeding Parasites

Ticks (Ixodida order) is one of the most important groups of blood-feeding arthropods worldwide. Unlike fleas or bed bugs, which cause irritation mainly in homes, ticks pose a dual threat: they feed on blood and are major vectors of human and animal diseases. Their small size, stealthy feeding behavior, and ability to transmit pathogens make them a serious concern for public health, veterinary medicine, and outdoor enthusiasts.

Ticks (Ixodida order) is one of the most important groups of blood-feeding arthropods worldwide. Unlike fleas or bed bugs, which cause irritation mainly in homes, ticks pose a dual threat: they feed on blood and are major vectors of human and animal diseases. Their small size, stealthy feeding behavior, and ability to transmit pathogens make them a serious concern for public health, veterinary medicine, and outdoor enthusiasts.

Ticks are not insects but arachnids, related to spiders and mites. With more than 900 recognized species, ticks are found on every continent except Antarctica. Some of the most impactful species include the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), responsible for Lyme disease in North America; the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), linked to Rocky Mountain spotted fever; and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), known for causing meat allergy.

This article explores everything about ticks: their identification, biology, global distribution, the diseases they transmit, and strategies for prevention and control.

Identification

Ticks can be recognized by their distinctive body structure and feeding habits.

-

General features:

-

Flat, oval bodies that expand dramatically when engorged with blood.

-

Eight legs (larvae have six legs, nymphs and adults have eight).

-

Hardened mouthparts called a hypostome with backward-facing barbs for anchoring.

-

No wings or antennae, unlike insects.

-

-

Common species of concern:

-

Blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis): Small, dark brown; main vector of Lyme disease.

-

American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis): Brown with mottled gray markings.

-

Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum): Females have a distinct white spot on their back.

-

Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus): Often found indoors, associated with kennels and homes.

-

Misidentifications: Tick bites are sometimes confused with mosquito or chigger bites, but ticks remain attached for hours or days, unlike other biting pests.

Biology and Ecology

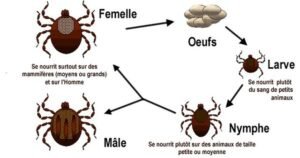

Ticks have a three-host life cycle in most species: larva, nymph, and adult. Each stage requires a blood meal before molting to the next.

Ticks have a three-host life cycle in most species: larva, nymph, and adult. Each stage requires a blood meal before molting to the next.

-

Eggs: Female ticks lay thousands of eggs in soil or leaf litter.

-

Larvae: Known as “seed ticks,” these six-legged forms feed on small animals like rodents and birds.

-

Nymphs: Eight-legged and larger, they feed on medium hosts including humans, cats, and dogs.

-

Adults: Seek large hosts such as deer, livestock, dogs, and humans. Females need a final blood meal before laying eggs.

Feeding behavior:

Ticks insert their barbed mouthparts deep into skin and secrete anticoagulants and anesthetics, making bites painless at first. Feeding can last several days, increasing the chance of pathogen transmission.

Environmental preferences:

-

Moist, shaded environments: leaf litter, tall grass, wooded trails.

-

Seasonal activity peaks in spring and summer, but some species remain active year-round in warm climates.

Global Distribution

Ticks are found across nearly all ecosystems.

-

North America: Lyme disease is concentrated in the northeast and upper Midwest, while Rocky Mountain spotted fever occurs more in the south-central U.S.

-

Europe: Species like Ixodes ricinus are the primary vectors of Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis.

-

Asia: Home to species transmitting severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) and other viruses.

-

Africa: Rhipicephalus ticks spread ehrlichiosis and East Coast fever in cattle.

-

South America: Several Amblyomma species impact livestock and wildlife.

Global warming and changes in land use are expanding the ranges of many tick species into new regions.

Risks and Damage

Ticks are infamous for disease transmission. Major examples include:

-

Lyme disease: Caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, spread by blacklegged ticks in North America and Ixodes ricinus in Europe.

-

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF): Caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, mainly spread by American dog ticks.

-

Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis: Bacterial infections with flu-like symptoms, spread by Ixodes and Amblyomma ticks.

-

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE): Viral disease in Europe and Asia.

-

Alpha-gal syndrome: Lone star tick bites can trigger an allergy to red meat.

-

Babesiosis: Parasitic infection affecting red blood cells, transmitted by Ixodes scapularis.

Other consequences:

-

Skin irritation and itching.

-

Secondary infections if bites are scratched.

-

Tick paralysis in rare cases, caused by neurotoxins in tick saliva.

-

Economic impact on livestock through reduced weight gain, milk production, and mortality.

Signs of Infestation

On humans:

-

Attached ticks after outdoor exposure.

-

Circular rashes (erythema migrans) in Lyme disease.

-

Fever, fatigue, or joint pain following bites.

On pets:

-

Engorged ticks visible on ears, neck, or between toes.

-

Persistent scratching and irritation.

-

Anemia in severe infestations.

In the environment:

-

High deer or rodent activity usually correlates with heavy tick presence.

-

Dragging a white cloth through grass (tick drag test) reveals their presence.

Control Methods

Personal protection:

-

Wear long sleeves, pants tucked into socks, and light-colored clothing.

-

Apply repellents with DEET, picaridin, or permethrin (clothing treatment).

-

Perform full-body tick checks after outdoor activity.

-

Shower within 2 hours of being outdoors.

On pets:

-

Use veterinarian-approved preventives: oral medications, spot-on treatments, or tick collars.

-

Groom pets regularly to detect ticks early.

Environmental measures:

-

Keep lawns short and clear of leaf litter.

-

Place gravel or woodchip barriers between yards and wooded areas.

-

Manage deer populations where feasible.

Chemical control:

-

Acaricides can be applied to lawns and high-risk areas.

-

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) combines chemical and non-chemical approaches.

Advanced Approaches

-

Biological control: Research into fungi such as Metarhizium anisopliae and nematodes that infect ticks.

-

Host-targeted devices: Wildlife feeders that apply acaricides to deer or rodents.

-

Vaccines: Experimental vaccines against tick saliva proteins or tick-borne pathogens.

-

Landscape modeling: Using satellite imagery and climate data to predict tick hotspots.

-

Genetic research: Studying tick microbiomes to reduce their ability to transmit pathogens.

Cultural and Historical Context

Ticks have appeared in folklore, literature, and medicine for centuries.

-

In medieval Europe, unexplained fevers from tick bites were often attributed to “forest curses.”

-

In Native American traditions, ticks symbolized persistence but were also feared as parasitic spirits.

-

In modern times, ticks feature in public health campaigns, documentaries, and even news headlines due to expanding ranges and unusual cases like red meat allergy.

Ticks embody the tension between nature and health, serving as reminders of the invisible risks in outdoor environments.

FAQ

Q1: How long can a tick stay attached?

Depending on the species, ticks can feed for 3–10 days if undisturbed.

Q2: Can ticks survive indoors?

Most ticks prefer outdoor environments, but brown dog ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) can infest homes and kennels.

Q3: What’s the best way to remove a tick?

Use fine-tipped tweezers, grasp close to the skin, and pull steadily upward. Avoid twisting or crushing.

Q4: Do ticks jump or fly?

No. Ticks wait on vegetation and climb onto passing hosts. They do not fly or jump like fleas.

Q5: What diseases do ticks transmit to dogs?

Dogs can contract Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis.

Q6: How can I make my yard tick-safe?

Mow grass regularly, remove brush piles, create gravel barriers, and apply acaricides if infestations are severe.

Final Thoughts

Ticks (Ixodida) are among the most resilient and dangerous external parasites affecting both humans and animals. Unlike fleas or mosquitoes, which feed quickly and leave, ticks remain attached for days, increasing the risk of transmitting pathogens. Their role in spreading Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, anaplasmosis, and other illnesses highlights their importance in global public health.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Personal protection, pet treatments, and environmental management significantly reduce exposure. In regions with high tick populations, awareness campaigns and integrated pest management (IPM) approaches provide long-term solutions.

Looking ahead, scientific research into vaccines, biological control, and microbiome manipulation may redefine how we manage ticks and tick-borne diseases. Until then, vigilance, education, and early detection are the keys to keeping families and pets safe.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only. Pest control laws and approved chemicals vary by country. For best results and legal safety, we strongly recommend contacting a licensed pest control professional in your local area. Always make sure that the pest control technician is properly certified or licensed, depending on your country’s regulations. It’s important to confirm that they only use approved products and apply them exactly as instructed on the product label. In most places in Europe, UK, or USA, following label directions is not just best practice—it’s the law.

Author Bio

Nasos Iliopoulos

BSc Agronomist & Certified Pest Control Expert

Scientific Director – Advance Services (Athens, Greece)

Licensed Pest Control Business – Ministry of Rural Development & Food (GR)